Author: Hamza Shad

-

Rediscovering a Forgotten Partition-Era Letter

In a recent trip to our family home, my mom rediscovered an old postcard addressed to my great-grandfather, Mohammad Ali Mirza. The letter was sent to him on October 17, 1947 in the aftermath of the partition of British India by his Hindu friend Diwan C. Khanna, who had to flee from Lahore to Delhi.…

-

Review: Stories of Your Life and Others

[This article contains mild spoilers.] Recently, I watched the movie Arrival (released in 2016) and was impressed by its philosophical profundity and intellectual portrayal of first contact with aliens. The movie keeps you in suspense throughout and makes you think deeply even long after it’s over. As someone interested in languages, I appreciated the substantial time it…

-

Top 5 Versions of “Tajdar-e-Haram”

In no particular order, here is my list of the top five versions of the qawwali “Tajdar-e-Haram”. You can find my full translation of the poetry here. The original by the Sabri Brothers is obviously very hard to match, but I think others have also done justice to it. Post any more versions of “Tajdar-e-Haram” that you enjoy in…

-

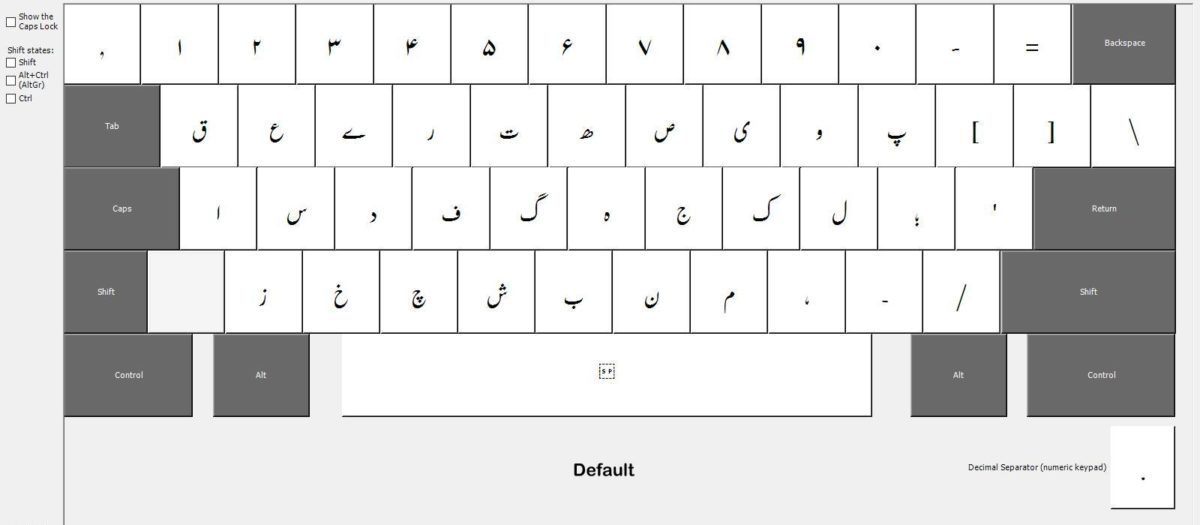

A Comprehensive Keyboard Layout for Urdu

Many Urdu speakers first learn how to type in English, and therefore have trouble adjusting to the standard Urdu keyboard layout. The same applies to many of the speakers of languages that use variations of the Arabic script. Some people adjust to the standard layout of the language, but others may prefer an alternative that is…

-

Urdu: Language of Poets

Urdu is an Indo-European language from the central zone of the Indo-Aryan branch, with over one hundred million speakers worldwide. Once associated with the Mughal Empire, it is most prominent in Pakistan, northern India, and South Asian diaspora communities. Due to its mutual intelligibility with Hindi, Urdu and Hindi are often referred to jointly by the term…

You must be logged in to post a comment.